Preparation

and structure of titanate nanotubes

D. Králová 1, E. Pavlova 1,

M. Šlouf 1,2, R. Kužel 3

1Institute

of Macromolecular Chemistry, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic,

Heyrovskeho nam. 2, 162 06 Praha 6,

2Member of Consortium for Research of Nanostructured and Crosslinked Polymeric Materials (CRNCPM)

3Department

of Electronic Structures, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics,

121 16 Praha 2, Ke Karlovu 5,

kralova@imc.cas.cz

Keywords: TiO2, titanate nanoparticles, nanotubes,

electron diffraction.

Abstract. This

work describes simple and reproducible preparation of dried and stable titanate

nanotubes (Ti-NT) in gram-scale amounts using freeze drying. Ti-NT represent a

novel type of nanoparticles with interesting morphology and peculiar structure.

The morphology, crystalline structure and elemental composition of Ti-NT were

investigated by means of scanning and transmission electron microscopy, X-ray

and electron diffraction and X-ray diffraction.

Introduction

In the past decade, fabrication of various inorganic nanoparticles has attracted much attention because of their interesting properties and potential applications. Several recent studies have reported a synthesis of a novel type of TiO2-based nanoparticles, whose morphology and crystal structure is completely different from common TiO2 modifications [1, 2, 3]. Hollow tubular nanoparticles, denoted as titanate nanotubes (Ti-NTs), are formed by a rolled sheet. Majority of authors agree that the plane of a single sheet is formed by octahedrons, identically to well known TiO2 crystal modifications, such as anatase, rutile and brookite. Nevertheless, the structure and composition of Ti-NT remain unclear and also formation mechanisms of Ti-NTs has not been fully clarified yet [4,5,6,7].

For many potential applications of Ti-NT in materials science it is essential to obtain dry, well separated, chemically and morphologically stable nanoparticles. As for morphological stability, the key point is to preserve single character and high aspect ratio of the particles, i.e. the breaking and the merging of the particles should be minimized. Nonetheless, the authors of available literature focus their attention on structure of single nanotubes [3,8,9,10], their thermal stability [11,12] or conductive properties [13,14].

The aim of this study was to develop a straightforward, reproducible preparation technique yielding dried, non-destructed Ti-NTs in gram-scale amounts. Synthesis of Ti-NT was based on hydrothermal treatment of TiO2 powder in concentrated NaOH solution described elsewhere [2]. Three parallel syntheses and three different drying procedures were performed. The morphology of Ti-NT was investigated by means of scanning and transmission electron microscopy, their crystalline structure was studied by X-ray and electron diffraction and their elemental composition by energy-dispersive X-ray analysis.

Experimental

Synthesis and drying of Ti-nanotubes. Titanate

nanotubes (Ti-NT) were synthesized by hydrothermal treatment as reported in

literature [1,2]. Starting TiO2 modifications included: technical

powder (Riedel-de Haën, Sigma-Aldrich), anatase TiO2 powder (99, 8%;

Aldrich) or TiO2 nanopowder (99, 9%, Aldrich); the other chemicals

used were NaOH (Lach-Ner, s.r.o.), HCl (35% p.a., Lach-Ner, s.r.o.) and deionized

water.

Ti-NT

were prepared by three parallel syntheses (denoted as S20, S28 and S30).

Briefly, 6 g of TiO2 powder in 10M NaOH aqueous solution in a closed

vessel was heated at 120 °C for 20 hours and subsequently washed with water to

achieve pH = 11.5 (sample denoted S30/11,5). Part of solution was neutralized

by 0,1M HCl aqueous solution and subsequently washed with water to pH = 5.5

(sample denoted S30/5,5). The remnant of solution (S30) and solution another

synthesis (S20) were dried in six different ways: S20 was filtered and dried on

air for 20h (S20/D1), dried at 60 °C for 2 hours (S20/D2), dried at 60 °C for 4

hours (S20/D3), dried at 100 °C for 4 hours (S20/D5) and dried at 60 °C for 4

hours under the vacuum (S20/D6). Part of Ti-NT suspension was dispersed in

ethanol, filtered and dried on air for 20 hours (S20/D4) or dried at 60 °C for

4 hours (S20/D7). The rest of S30 was more diluted by distillated water and

freeze died (S28/L1, S30/L1).

Specimens

for electron microscopy were prepared as follows: Ti-NT dispersion in water or

dried Ti-NTs was dispersed in water. In some cases the Ti-NT were treated in

ultrasonic bath for several minutes. The impact of sonication on the Ti-NT

structure was examined using the samples sonicated from 1 minute to 25 minutes.

Scanning electron microscopy and microanalysis. The

morphology of Ti-NT powders was characterized by scanning electron microscopy

(SEM) using a high resolution, field-emission gun SEM microscope Quanta 200 FEG

(FEI, Czech Republic) equipped with energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS).

Specimens for morphological investigations (SEM) were prepared by drying of a droplet

of Ti-NT dispersion on the carbon support.

The specimens were then observed as they were in low-vacuum mode using

accelerating voltages from 10 to 30 kV. Specimens for X-ray microanalysis (EDS)

were prepared by consolidation of dry Ti-NT into tablets. EDS spectra were

collected from several locations at each tablet at acceleration voltage 30 kV.

Transmission electron microscopy and electron

diffraction. The morphology of Ti-NT powders was

simultaneously inspected by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and crystal

structure was analyzed electron diffraction (ED) using a 120 kV TEM microscope

Tecnai G2 Spirit (FEI,

Powder X-ray diffraction. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD). The measurements of whole patterns

were performed mainly on XRD7 (FPM-Seifert) diffractometer with monochromator

in the diffracted beam.

Results and

discussion

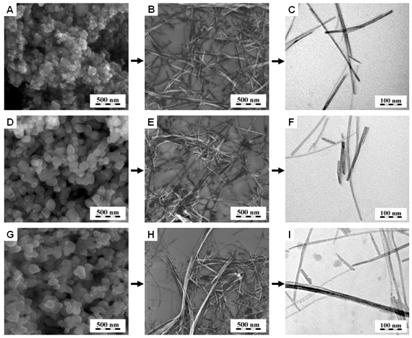

Suspension of titanate nanotubes, Ti-NT, have been prepared from TiO2 powders by standard method described in the literature [1,2,3]. We repeatedly succeed in preparing Ti-NT from a mixture of different types TiO2 crystal modifications (Fig. 1) not only from pure anatase as stated in some papers [3]. The amount, morphology and structure of Ti-NT were not affected by the modification of starting TiO2.

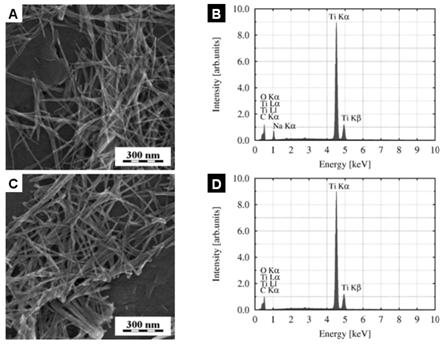

In

addition, the assumption that formation of nanotubes in aqueous solution is

completed after hydrothermal treatment was confirmed. In contrast to some

studies [1, 2, 15], we show that neutralization by HCl is not necessary for

their formation (Fig. 2). The Ti-NT were observed both after washing with water

(Fig. 2a) or HCl (Fig. 2b). It was also proved by EDS that Na+ ions

are not necessary to stabilize Ti-NT, which persist both in presence (Figs.

2a-b) or absence (Figs 2c-d) of sodium.

Nevertheless, it was observed that the stability of Ti-NT decreases from

several months in strong alkaline solutions to several weeks in solutions with

lower pH. Ti-NT are further impaired if they are transferred to non-aqueous

medium as evidenced by both SEM and TEM.

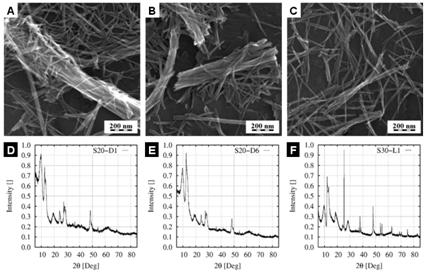

Drying

procedure is a critical step to obtain gram-scale amounts non-destructed Ti-NT

because the nanotubes tend to merge and break when they are isolated from

solution. This was proved by examination of seven different ways of drying in

air and in vacuo, as described in

experimental section. Representative electron micrographs of air drying (Fig.

3a) and vacuum drying (Fig. 3b) showed agglomeration and merging of the

nanotubes, which decreased their desirable high aspect ratio. The crystalline

structure of Ti-NT did not change as proved by PXRD (Figs. 3c-d). During

freeze-drying the external morphology of Ti-NT was similar to that observed

after drying in air or vacuum but the nanotubes were much less agglomerated and

merged (compare Fig. 3a-b with Fig. 3c). However, PXRD results proved that the

internal crystalline structure of freeze-dried Ti-NT was completely different

(compare Figs. 3d-e with Fig. 3f).

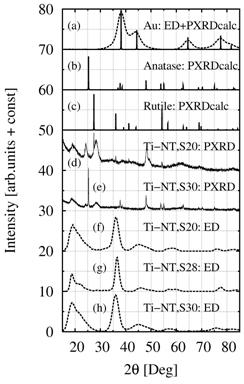

The PXRD

results were compared with simulated powder diffraction patterns (calculated by

program PowderCell, [16]) and experimental ED diffraction patterns (processed

by program ProcessDiffraction, [17]). Reliability and precision of ED in our

TEM microscope was verified by means of standard Au specimen (Fig. 4a).

Theoretical powder diffraction patterns of anatase and rutile were calculated

with program PowderCell (Fig. 4b-c). Experimental PXRD results from previous

experiments were included for comparison (Figs. 4d-e). Finally, ED diffraction

patterns from all three parallel syntheses (S20, S28, S30) were collected

(Figs. 4f-g). Comparison of all diffraction patterns in Fig. 4 clearly showed

that the crystalline structure of Ti-NT was different from both common TiO2

modifications. Surprisingly enough, all three ED patterns of Ti-NT are the

same, whereas PXRD patterns of Ti-NT from syntheses S20 and S30 differ both

from each other and from the corresponding ED patterns. There are two tentative

explanations: (a) All different Ti-NT are changed in the electron microscope

due to very high vacuum and interaction electron beam. (b) ED patterns were recorded

from a small selected area of the specimen, where it was possible to observe a

transparent layer of single nanotubes. It is possible that structure of these

nanoparticles remained the same, while bigger Ti-NT agglomerates, whose

reflections dominate PXRD patterns, undergo structural changes. In any case,

this discrepancy will be a subject of our further study.

We

studied possibilities to improve dispersion of Ti-NT by sonication before

drying. SEM micrographs demonstrated that sonication of Ti-NT in solution

yields less merged nanotubes but, sonication times higher than 5 minutes break

the nanotubes (Fig. 5). As a result, we used in all experiments zero or very

short sonication times.

Conclusion

Titanate nanotubes (Ti-NT) were prepared using a hydrothermal synthesis described elsewhere. Ti-NT represent a novel type of nanoparticles with peculiar structure. In this study we show that gram-scale amounts of Ti-NT can be isolated from solution by freeze drying.

Three parallel syntheses and three drying procedures were used to prepare dried Ti-NT in gram-scale amounts. Impact of preparation and drying on external morphology and internal crystal structure of Ti-NT was investigated by microscopic (SEM, TEM, EDS) and diffraction (PXRD, ED) methods.

SEM and TEM micrographs showed that the Ti-NT are quite stable, especially if they are kept in alkaline solution. The basic morphology of the nanotubes does not change, their diameters are approx. 10 nm and their lengths are usually in micrometer scale. Nevertheless, during drying the nanotubes tend to break and merge, which decreases their high aspect ratio that is advantageous for many potential applications in materials science.

PXRD and ED proved that the breaking and merging of nanotubes during drying has only negligible effect on internal crystalline structure if we apply standard drying in air or vacuum. Freeze drying limits breaking and merging of the nanotubes but changes the crystalline structure of Ti-NT. None of the observed Ti-NT crystalline structures corresponded to common crystal modifications of TiO2.

It has been demonstrated that freeze drying is the best technique to prepare high amounts of dried, single, non-merged Ti-NT with high aspect ratio.

References:

[1] T. Kasuga, M. Hiramatsu, A. Hodin, T. Sekino, K. Niihara, Langmuir 14 (1998), 3160.

[2] T. Kasuga, M. Hiramatsu, A. Hoson, T. Sekino, K. Niihara, Advanced Materials 11 (1999), 1307.

[3] Y.-F. Chen, Ch.-Y. Lee, M.-Y. Yeng, H.-T. Chiu, Materials Chemistry and Physics 81 (2003), 39-44.

[4] G.H. Du, Q.

Chen, R.C. Che, Z.Y.Yuan, L.-M. Peng, Applied Physics Letters 79 (2001) 3702.

[5] Y.Q. Wang,

G.Q. Hu, X.F. Duan, H.L. Sun, Q. K. Xue, Chemical Physics Letters 365 (2002)

427.

[6] R. Ma, Y.

Bando, T. Sasaki, Chemical Physics Letters 380 (2003) 577.

[7] Ch.-Ch. Tsai, J.-N. Nian, H. Teng, Applied Surface Science 253 (2006) 1898.

[8] R. Ma, Y. Bando, T. Sasaki, J. Phys. Chem. B 108 (2004) 2115.

[9] Ch.-Ch. Tsai, H. Teng, Chem. Mater. 18 (2006) 367.

[10] T. Kašuba, Thin Solid Films, 496 (2006), 141.

[11] L.-Q. Weng, S.-H. Song,

[12] E. Morgado Jr., M. A.S. de Areu, O. R.C. Pravia, B. A. Marinkovic, P. M. Jardim, F. C. Rizzo, A. S. Araújo, Solid State Science 8 (2006) 888.

[13] M. Zhang, Z. Jin, J. Zhang, X. Guo, J. Yang, W. Li, X. Wang, Z. Zhang, Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical 217 (2004) 203.

[14] J. Yu, H. Yu, B. Cheby, C. Trapalis, Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical 249 (2004) 135.

[15] Ch.-Ch. Tsai, H. Teng, Chem. Mater. 16 (2004) 4352.

[16] http://www.ccp14.ac.uk/tutorial/powdcell/index.html

[17] J. L. Lábár, Microscopy and Analysis, 75 (2002) 9-11.

The authors are

indebted for financial support trough grant GACR 203/07/0717. MŠ acknowledges

the participation in the EU Network of Excellence Nanostructured

Multifunctional Polymer Based Materials and Nanocomposites (NANOFUN-POLY). The work is also a part of

the research programs MSM 0021620834.

Figure 1. Synthesis of Ti-NT from various sources: (a,b,c) TiO2 nanopowder -mixture of anatase and rutile, (d,e,f) technical TiO2 - mixture of rutile and anatase and (g,h,i) TiO2 powder - anatase modification. SEM micrographs of original powders (a,d,g), SEM/TEM micrographs of Ti-NT (b,e,h/c,f,i).

Figure

2.

Synthesis of Ti-NT from solutions with various pH: (a,b) pH = 11.5 and (c,d) pH

= 5.5. SEM micrographs (a,b) and corresponding EDS spectra (b,d).

Figure

3.

Influence of drying on Ti-NT external morphology and internal crystalline

structure. (a,d) drying in air - sample S20-D1, (b,e) drying in vacuum - sample

S20-D6, (c,f) freeze drying - sample S30-L1. SEM micrographs (a,b,c) and

corresponding PXRD patterns.

Figure

4.

Comparison of experimental and calculated diffraction patterns of Ti-NT. (a)

experimental ED and calculated PXRD of standard Au specimen, (b) calculated

PXRD of anatase, (c) calculated PXRD of rutile, (d) experimetal PXRD of Ti-NT,

synthesis S20-D2, (e) experimental PXRD of Ti-NT, synthesis S30-L1, (f,g,h)

experimental ED of Ti-NT, syntheses S20-D2, S28-L1, S30-L1.

Figure

5.

Impact of sonication on morphology of Ti/NT. Sonication for (a) 1 min, (b) 5

min, (c) 15 min and (d) 25 min. More than 5 min of sonication breaks the

nanotubes.