Kutna Hora

Take a

walk around Kutná Hora and discover the history of the town that used

to stand just behind the royal City of Prague some centuries ago, town

that was called the jewel and the treasury of the country, town whose

wealth elevated the Czech kingdom on the pedestal of fame and power.

The

origins of Kutná Hora are usually linked with the development of

monetary economy in the 13th century, however, the dawn of mining came

a lot earlier. Surface traces of silver ore were probably discovered in

the late 10th century by the Slavníks who had small silver coins –

denars – struck at their settlement in Malín, today a part of Kutná

Hora.

After

the initial vagueness in historical facts, let’s proceed directly to

the discovery of local ore deposits. From the technical point of view,

silver was discovered by prospectors that systematically surveyed the

area of Českomoravská Vrchovina highlands. The first tangible

record of mining and processing of silver ore in the 13th century is a

nameless hamlet near Malín, which we have archaeological remains of.

Rumours about rich silver deposits attracted new settlers, thousands of

which were coming to the area mostly from neighbouring German speaking

regions, bringing along advanced manufacturing technology and social

system and thus becoming the leading group in the entire agglomeration.

Immediate surroundings of particular shafts saw the construction of

provisional dwellings, wooden chapels and primitive winding equipment.

The atmosphere of Kutná Hora at that time may have resembled the

atmosphere of American gold-miner’s settlements; contemporary records

talk about a “rush to Kutná” and mention the fact that the fame of

local mines spread across the border of the country.

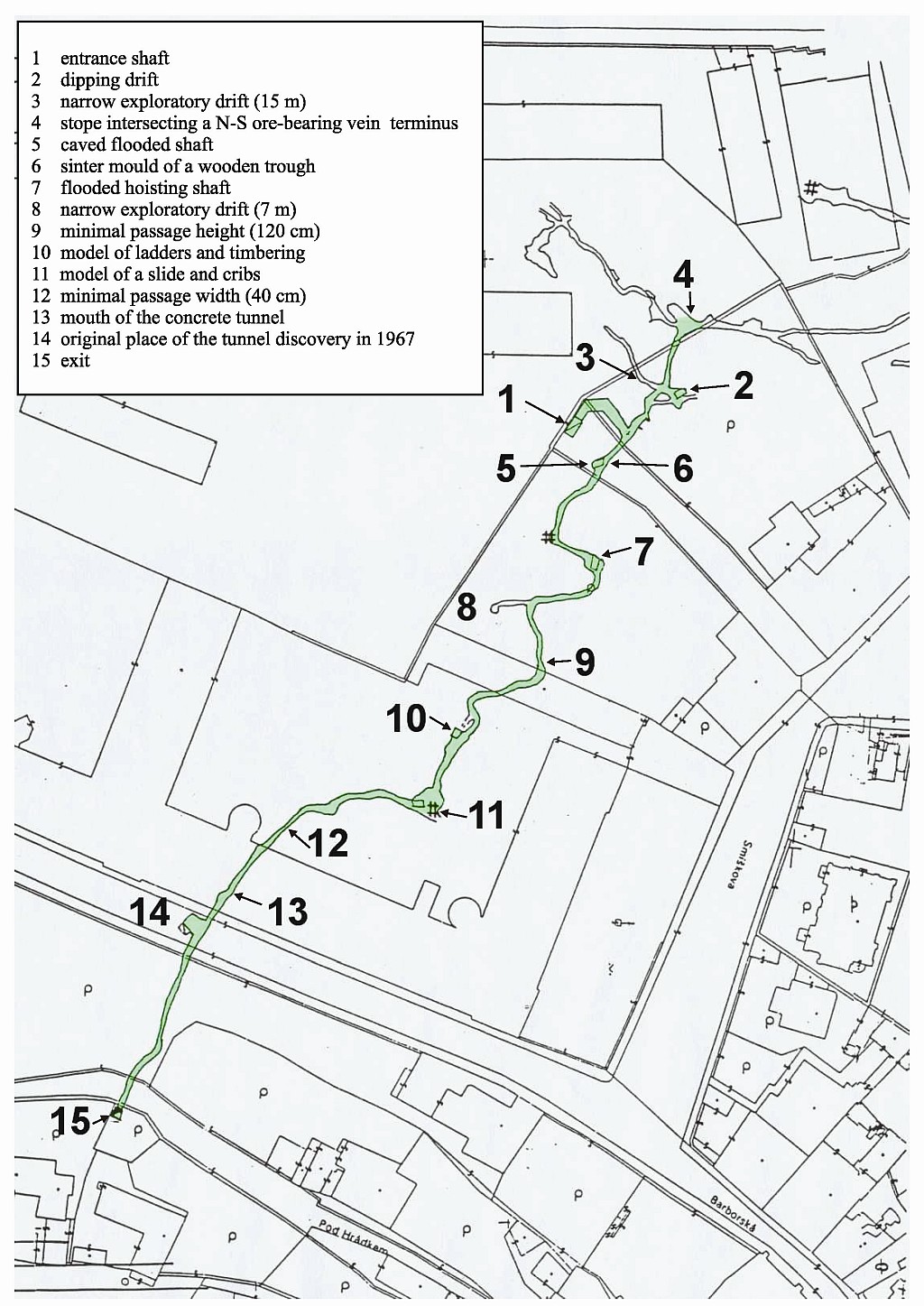

Medieval Silver Mine

Part

of the mining-historical exposition of the Czech Museum of Silver is

also medieval mine located in the area between the main building of the

Museum - Hrádek.The mine was discovered in 1967 when a

hydro-geological exploration of the center of the town was carried out.

In the depth of approximately

22 m

an old gallery was discovered. At first the discoverers were convinced

it was the famous Osel (Donkey) mine that ranked among the deepest and

richest mines of Kutná Hora until the middle of the 16th century and

that was localised into this very area by written documents. But the

subsequent exploration showed it to be perfectly preserved medieval

drainage gallery, dug in a long period of time from the 14th until the

beginning of the 16th century. The oldest sections of this gallery

forming a complex floor of corridors above the flooded and still

unexplored large mine work originally connected individual mining pits

of the Osel and Čapčoch ore belts.

The

gallery was dug out in the gneiss of Kutná Hora crystallinic rocks

tightly by contact with base chalk conglomerates. Quartz and gneiss

nuggets of this conglomerate can be seen on many places on the roof. As

there are sediments containing calcite in the roof, similar phenomena

as in karst caves can be met in the gallery. Medieval miners used to

work by hands with two mining hammers – chisel and sledge-hammer.

Traces of these hammers can be seen on many places on the walls and the

roof of the corridor. Besides, there are copious small niches dug out

in the walls into which miners used to put away their pit lamps. About

250 m

of the gallery are accessible to visitors. Theys walk through the

medieval mine in canvas white kirtle, so called perkytle –

traditional clothing of miners, with helmet and lamp.

Hrádek

Almost

for 7 centuries Hrádek - eyewitness of the beginning of the town of

Kutná Hora - overlooks the valley of the river Vrchlice. It was

standing here probably already before the silver rush attracted

entrepreneurs and adventurers into this area and brought into existence

a mining town, “second in the land right after Prague”.As a wooden

fortress, Hrádek towered above a slope, from which it guarded a trade

route crossing the countryside. At the turn of the 13th and the 14th

century, it was joined on the slope by a fortified manor-house built up

for purposes of newly established central royal mint, the Italian Court

of later.A long and eventful history awaited Hrádek. Wooden, probably

fortified redoubt transformed at the time, when the Czech king himself

was building his residence in the mint of Kutná Hora, into stone

palace of urban style, which came into possession of Václav of Donín,

a favourite of king Václav IV.

Italian Court

The

origins of the Italian Court are shrouded in mystery and historians can

only guess because no written resources and only a few artefacts dating

from the earliest history of the building have been preserved.

Presumably there used to be a little fortified castle that was later

chosen by the sovereign to become the seat of the new Central Mint.

Since the very beginning, the Italian Court was separated from the town

by fortified moats to protect the workshops, in which silver was

processed and coins were struck. The original building was

reconstructed at the turn of the 15th century, allegedly upon the

request of King Wenceslas II, and the chapel and the royal palace were

added. Fires accompanying the Hussite wars probably avoided the Italian

Court at all and thus it was able to retain its representative

appearance enabling to welcome significant visitors and host royal

assemblies. Another restoration was initiated by King George of Poděbrady

at the time of reintroduction of Prague Groschen. Jan Horstoffar of

Malešice, the ambitious highest mintmaster, had the adjacent

mintmaster’s house built at the end of the 15th century; he also

refurnished the chapel by purchasing new panel altars from Nuremberg,

his native town. Reconstruction activities were managed by Matyas

Rejsek. From the Baroque period dates only the fountain in the

courtyard (1739) and a few details. The Italian Court thus remained

virtually unchanged until the end of the 18th century, when the mint

and the mining office were abolished and the building began to decay. A

century passed and the condition was critical, some people even called

for its demolition. Eventually in the 1880s, municipal authorities

decided to carry out a vast reconstruction project under the direction

of the famous architect Ludvík Lábler. That involved mainly the

removal of ruined workshops; what remained were the royal palace, the

treasury and the chapel that was redecorated in the Art Nouveau style

by František and Marie Urban. Despite all transformations, the Italian

Court is one of the most valuable monuments of Kutná Hora. Its

neo-Gothic reconstruction is a great example of cultural preservation

methods and techniques a hundred years ago.

Cathedral

of St. Barbara

This

five-aisled Gothic cathedral is arguably the second most significant

church in the Czech Republic after the Cathedral of St. Vitus in

Prague. It was established as miners’ church which is documented by

its dedication to St. Barbara, the patroness of miners. The

construction was not finished until the break of the 19th and 20th

centuries. All around the church, rich sculptural and stone-mason late

Gothic decoration has been preserved; in some places, late Gothic wall

paintings have been preserved. There is Corpus

Christi Chapel near the cathedral - a square,

three-aisled space which was intended as ossuary. However, when Jesuits

were established in town in the 17th century, it started to be called

Corpus Christi Chapel because Holy Sepulchre was exhibited there at

Easter.

Stone

House

The

most famous burgher structure of Kutná Hora, the Stone House dates

back to the pre-Hussite period, traces of which are still to be seen in

the cellars. In the 1460s, the house went in the hands of the Kroupa

family; as Prokop Kroupa became the highest mining official in the town

in the 1480s and received the noble title of Chocemice, he decided to

rebuild it to a sumptuous patrician residence. The golden age of the

Stone House thus began in 1489 and the reconstruction was assigned to

Master Briccius Gauske, builder of the town hall in Wroclaw, Silesia,

in which he found inspiration for many architectural elements of

Prokop’s residence, especially for its remarkable front fasade. At

first glance you will notice the distinct oriel, but it is mainly the

triangular gable that ranks among the masterpieces of Czech Gothic

architecture. It is lined by a moulding decorated by a relief with

pastoral motifs. Above the moulding are knights fighting in a

tournament to remind of Prokop’s nobility. The crest of the miners’

guild indicates the source of Prokop’s fortune and the municipal

coat-of-arms is to emphasize the importance of Kutná Hora. The top of

the gable is decorated with Virgin Mary on the Throne with Christ and

two angels holding her crown above her. On both sides, there are

statues of Adam and Eve under the Tree of Knowledge. Current appearance

of the fasade bears traces of the puristic restoration of the building

at the end of the 19th century; since the restoration the Stone House

has housed a museum with both permanent and temporary expositions.

Stone

Fountain

In

its struggle for self-presentation, Kutná Hora was not content with

simple public structures designed just to meet their purpose, the

municipality called for something extra. Such buildings included mainly

the monumental Town Hall built by Matyas Rejsek after 1490 – however,

that has not been preserved – and the Stone Fountain, burghers’

wordless tribute to water. That is to say water was always lacking in

Kutná Hora, therefore bringing a rich spring through a system of

wooden pipes right into the heart of the town was a creditable effort.

The Stone Fountain was built in 1495 and sometimes it is also ascribed

to Matyas Rejsek. This polygonal structure that was originally

decorated by a number of statues stands at a beautiful location on a

small square surrounded by a splendid complex of burgher houses.

Cementary

Chapel with Ossuary

A

cistercian monastery was founded near here in the year 1142. One of the

principal tasks of the monks was the cultivation of the grounds and

lands around the monastery. In 1278 King Otakar II of Bohemia sent

Henry, the abbot of Sedlec, on a diplomatic mission to the Holy Land.

When leaving Jerusalem Henry took with him a handful of earth from

Golgotha which he sprinkled over the cemetery of Sedlec monastery,

consequently the cemetery became famous, not only in Bohemia but also

throughout Central Europe and many wealthy people desired to be buried

here.The burial ground was enlarged during the epidemics of plague in

the 14 th century (e.g.in 1318 about 30 000 people were buried here)

and also during the Hussite wars in first quarter of the 15 th.

century. After 1400 one of the abbots had a church of All -Saints

erected in Gothic style in the middle of the cemetery and under it a

chapel destined for the deposition of bones from abolished graves, a

task which was begun by a half blind Cistercian monk after the year

1511. The charnel-house was remodelled in Czech Baroque style between

1703 - I710 by the famous Czech architect, of the Italian origin ,Jan

Blažej SANTIM-Aichl. The present arrangement of the bones dates from

1870 and is the work of a Czech wood-carver, František RINT (you can

see his name, put together from bones, on the right-hand wall over the

last bench).Our ossuary contains the remains of about 40 000 people.

The largest collections of bones are arranged in the form of bells in

the four corners of the chapel. The most interesting creations by

Master Rint are the chandelier in the centre of the nave, containing

all the bones of the human body, two monstrances beside the main altar

and the coat-of arms of the Schwarzenberg noble family on the left-hand

side of the chapel.

Jesuit

College

The

monumental Jesuit College was build according to plans by the famous

Baroque architect Domenico Orsi just next to St. Barbara’s Cathedral

between 1667 and 1703. Orsi designed an F-shaped ground plan to remind

of Habsburg kings Ferdinand II and Ferdinand III. The appearance is

quite austere, complying to Jesuit principles, only the front façade

resembles Italian palaces of the early Baroque period. The middle one

of the original three towers had to be removed for static reasons in

the mid-19th century. The artificial terrace in front of the College

was enclosed by a low wall with 13 sculptures of saints favoured by the

Jesuits, including St. Ignatius of Loyola, St. Franz Xaverius, St.

Wenceslas and others. It was designed as a free resemblance of the

Charles Bridge in Prague, which linked the seat of the Jesuit order in

Prague, Klementinum, with its temple – St. Vitus’s Cathedral in

Prague Castle. The statues were created by the Jesuit František

Baugut, author of the Plague Column, during the years 1703 – 1716.

|